For a brief moment on our daily walk around the house the other day, sun and rain and warmth coexisted, and it felt like spring might be here.

Author: Picking My Battles

Are You Our Mama?

It was almost uncomfortably warm on Saturday so we let the chicks into the chicken tractor to play while they’re current enclosure was cleaned. It was a good chance for them to really meet Jim, Princess Jane, and Katie.

Jane and Jim inspected the chirping babies and, discovering that the tractor was secured by wiremesh at all sides, spent most of the day feigning interest in a chipmunk hunt.

I sat with the chicks for a while, cleaning some garden implements and getting them used to the idea of me as Mother Hen. Eternally loyal, Katie sat with me. As she moved, the chicks often moved with her. She would sniff at them and wag her tail a little as they chirped at her.

The chicks came out of their eggs at the feed store, so the only “mamas“ they’ve ever known are a heat lamp and the changing hands that feed them. Katie was abandoned to a kill shelter as a puppy, and I doubt she had much contact with her mama.

Something in her past or her nature, however, made her loyal and gentle, more than a little bit of a pushover, and, when she has to be, brave. It seemed fitting that, for the moment, they saw her as the “Mother Hen.“

Ladies in Waiting

Princess Jane was much more welcoming than we expected when we opened the box of week-old chicks and gently deposited each one into the shaving-filed aquarium where they will live until they feather out. She had, after all, just come inside from disemboweling a chipmunk who made the mistake of venturing out of the woods, but it might have been her full belly that made it possible for her to treat the new arrivals — pullets all – as ladies in waiting rather than waiting dinner.

A Homesteader’s Dozen

It took less than a week of staying home to realize that, even with Thing1 home, we were saving piles of money by not eating out, not driving, not buying anything except what was on the grocery list. It took less than two weeks to remember that we could brush off our gardening skills and, without sending Thing1 to the Army (who wouldn’t take him and his malfunctioning immune system anyway), have some fun and make a sizable dent in that bill as well.

So the garden plan was drawn up. Seeds were started. And chicks were ordered.

We’ve had chickens in the past, and they’ve always been fun and educational . From the ladies, we’ve learned that it’s never too early or late to enjoy a good meal. From the roosters, our kids learned more about the facts of life than we were ready to explain. We learned a few unpleasant facts of life from the foxes, and the roosters learned the hard way not to pick on my chicks.

This time around we ordered pullets instead of a straight pick. We only need 6 but, wanting a few different breeds, we ordered the minimum 6 each of Rhode Island Reds and Americaunas from the feed store. Our chicken tractor will hold six comfortably (comfy chickens lay better eggs – seriously), so when they get bigger, we’ll give half of the flock to neighbors who want home grown eggs.

I’m calling it the Homesteader’s Dozen.

Drawing Lots

Pneumonia benched me well before Covid-19 invaded neighboring New York State, but my son’s severely compromised immune function was already forcing considerations about whether and how to keep working at the residential school where I teach.

Our school immediately implemented Herculean measures to reduce the likelihood of infection. The experiences of other assisted living communities across the nation, however, suggested that any infection, once introduced, would spread rapidly. I love my school kids, but knew working during the pandemic might mean living away from my family. When my body turned on me, I was almost grateful to surrender the decision and took a leave of absence as our family settled into the stay home directives that, while not all that new for most Vermonters, felt like a different normal.

When I started considering family safety, the virus was sweeping through cruise ships. There were a handful infections in Washington state, and the media zeitgeist was proclaiming that the virus “only” endangered the elderly and people with chronic illnesses (about 157 million people in the US), as if that made it more tolerable.

One night early in March, however, I caught an interview with Yale physician, Nicholas Christakis, predicting the trajectory the infection would soon take. Identifying schools as disease vectors (as any parent or teacher weathering flu and strep season can attest), he advocated nationwide closures. “Flatten the Curve“ hadn’t been coined, but he was articulating the strategy: slow the spread, reduce the load on the healthcare system, and improve the odds.

As March and the pandemic progressed, Christakis seemed like Cassandra delivering disturbingly accurate warnings, heeded only when case numbers and fatalities began to skyrocket.

I remember marveling at extraordinary examples of solidarity by people from all walks of life filling my Facebook feed when Americans did adopt the social distancing guidelines already in place in Europe. There were some doubting the seriousness of the disease or disregarding how their continued mobility might endanger others, but videos of people making masks, entertaining each other, organizing school services and lunches for kids and families were brief testaments that we were all at least trying to be in this together.

Then the economy, already wobbling under volatile oil futures and markets, imploded. Poorly maintained government safety nets struggled to expand and accommodate millions of newly unemployed people. Suddenly the stay home directives were not just about flattening an abstract curve, they were about individual rights, paychecks, and haircuts.

I don’t have much sympathy for people screaming for haircuts, but at least 40% of adults in the United States don’t have $400 on hand to cover an emergency. That means a lost paycheck could easily translate to a lost roof or food. In regions that have not yet seen spikes in the numbers, the prevention can easily seem worse than the disease.

I had just started programming in 1996 when I first saw a program crash because an end-user had tried to enter the date ‘2001’ in a two-digit year field. We fixed that particular issue pretty quickly, but as we went through our other programs, we realized how many applications were vulnerable. Y2K work wasn’t just bread and butter for the next few years, it was steak and caviar.

That New Year’s Eve, I brought home a laptop to login to work and monitor for any SNAFUs. As midnight rolled around, I wondered if many programs would fail. Would the “major” systems around the world make the jump successfully?

The next morning, there had been a few hiccups but no apocalypse. Newscasters seemed almost disappointed that more things hadn’t gone wrong, glossing over the fact that the millions of programmers who had been updating systems for the previous three or four years had made that possible.

Right now, people are being asked to accept hardships to make sure that as much of our worrying as possible is for ‘nothing’. Some people, even offering themselves as sacrifices, are willing to play the lottery and advocate for reopening the country. With one journal, however, suggesting that school closures alone prevent “only” 2-4% of Covid-19 related fatalities (2000-10,000 lives depending on projections) and new reports of hospitalizations and fatalities among younger, healthier people, reopening the “country” is a lottery that will trade lives for paychecks.

But too many missed paychecks can also cost lives.

Some (including me) would argue in favor of securing the social and digital safety nets to enable as many people as possible to stay home longer and reduce illness and contagion. People advocating the alternative, however, do have valid concerns. Safety nets are expensive. Any vaccine could be at least a year away. There’s no confirmation, yet, that surviving the disease confirms permanent immunity, meaning that this could be a question of thinning the herd rather than building herd immunity. Stay home directives could be simply delaying the inevitable.

Less than a century ago “The Lottery”, by Shirley Jackson, depicted a modern version of a “brutal ancient rite” taking place in some version of Bennington, Vermont. Townspeople drew lots to determine who would be sacrificed by stoning to ensure a good harvest. The New Yorker and Jackson received mountains of complaints and abuse from shocked readers who could not countenance the idea of even fictional human sacrifice in a modern setting.

We aren’t choosing lots or stoning people to death, but in the end, we are being asked not just what we personally are willing to surrender for the economy or a flatter curve. We are being asked who we are willing to sacrifice to achieve either goal. How many and which people are disposable?

On our very micro level, I know I would give my life to keep my kids safe and fed. I also know it’s easier to be a martyr than a problem solver. At some point, the pandemic and the economy will force us to ask the tougher question of how to balance Thing1’s health (and life) against my need to work, against Thing2’s right to go to school and grow. When do we “reopen”? We’ll find some answers in logistics. Other answers will require making ethical choices far more difficult than drawing lots.

Peas and Carrots

Peas and carrots are coming up in our straw bale garden. Carrots always seem to take a little while to germinate and don’t try my patience, but I confess, it never seems like spring until the first pea shoots appear.

This is the first year I’ve tried Strawbale Garden. Devised by a garden writer by the name of Joel Karsten, and it involves buying and arranging bales of, you guessed it, straw. You “condition” the bales by watering and feeding with organic fertilizer for a couple weeks before planting. then plant right in the bells, sometimes adding growing mix depending on the type of plant.

Health issues this year limited how much lifting and digging I had energy for, so ordering and arranging the straw bales was easy (especially with Thing1 doing most of the arranging). I’m always a little gun shy about ordering straw; you never know if you’ll get hay and weed seeds in there.

But this year, I’m game for an experiment.

I recycled weed barrier from the paths to cover the entire garden before bringing in bales. It’ll give it the summer to smother any weeds. We’ve gone scorched earth on the raspberry canes that were invading the area, and I’m planning to mulch the heck out of the space in the summer.

The appearance of peas and carrots in two of the bales gives me some hope. We’re putting in other greens today, the first truly warm day of spring. Peppers and tomatoes and other warm season vegetables are still under the lights in my office, And I feel like somebody just yelled, “Ladies, start your engines!“

Make Something Happy

Okay, okay, I take a lot of pictures of cats, especially happy cats.

The thing is, I was not especially happy just before I took this picture. I was angst-ing over work or money or a story I couldn’t get started, and then Jim-Bob, who had wedged himself on my lap under the computer, patted the laptop with his paw, and stretched out in the seam made by the afghan over my legs.

“Don’t worry,” he was saying. “I’m happy. Pet my head and you can be happy too.”

So I did, and just like Jimmy Durante promised, making that one something happy, for at least a few minutes made me happy too.

So here’s yet another happy cat picture that will hopefully make someone else happy.

How to be Real Cat

Real cats, according to Jim, don’t drink out of the water bowl. Drinking water, you see, is not really about hydration. Everything you do as a real cat should establish that everything in the place where you reside is belongs to you.

This is why, for example, when presented with a $.10 beer glass won at a fireman’s carnival, Jim preferred to push aside the flowers that were already there, jam his face into the glass and begin lapping at the water until the level is low enough for him to tip over the glass and spread the rest of the water around. This will teach the humans to exercise more care with “their” things that are actually his.

P. S. Jim was repeating this demonstration with a recycled tin can that currently serves as a watering can but got his face stuck inside the can. When I freed him from said can, he indicated in no uncertain terms that taking or posting any pictures of the fiasco would result in him peeing on everything I own. He would like everyone to know that the tin can still belongs to him.

Green Victorious

When I was a kid my parents and some friends rented a community garden plot in Baltimore. Our yard was mostly gravel and shade, and I remember the first summer my dad carrying on about the victory garden his parents had when he was a kid and the experience he wanted to replicate. We got a few salad and more zucchini then we could eat in 10 summers, and then we moved to a house with a big yard in the Midwest where, ironically, we grew only lawns and flowers. I’ve let my gardens lapse here and there, but this year, I have a hankering for victory.

I had my first back to the land epiphany when we moved to Vermont and wanted to make the most out of space. Every power outage and snowstorm that socked us in, every trip up our rutty road in mud season made me more determined to have my grocery store growing in my backyard, feeding my freezer through the summer. Whenever I dig in, however, I get a lot more than just groceries out of the dirt and my sweat.

My ongoing pulmonary issues and Thing1’s compromised immune system prompted us to initiate a ‘stay home’ protocol well before the governor issued one for everyone in our state. My body has limited how much heavy work I can do right now, but as long as I have the strength to whisper the words “I have an idea” to my husband (and now kids) the resurrection of a big garden was inevitable.

This year I’m experimenting with Straw-bale gardening, laying ground work for no-dig sheet mulching in the fall. So far the weather has been too cold to allow more than a few pea shoots to establish themselves in the conditioned bales, and trays of seedlings and propagated cuttings add welcome green to my office window.

The current experiment is much less work and may produce slightly fewer jars of tomato sauce. As long as there’s something green and hopeful flourishing, however, I’m calling this garden victorious.

Pole Beans

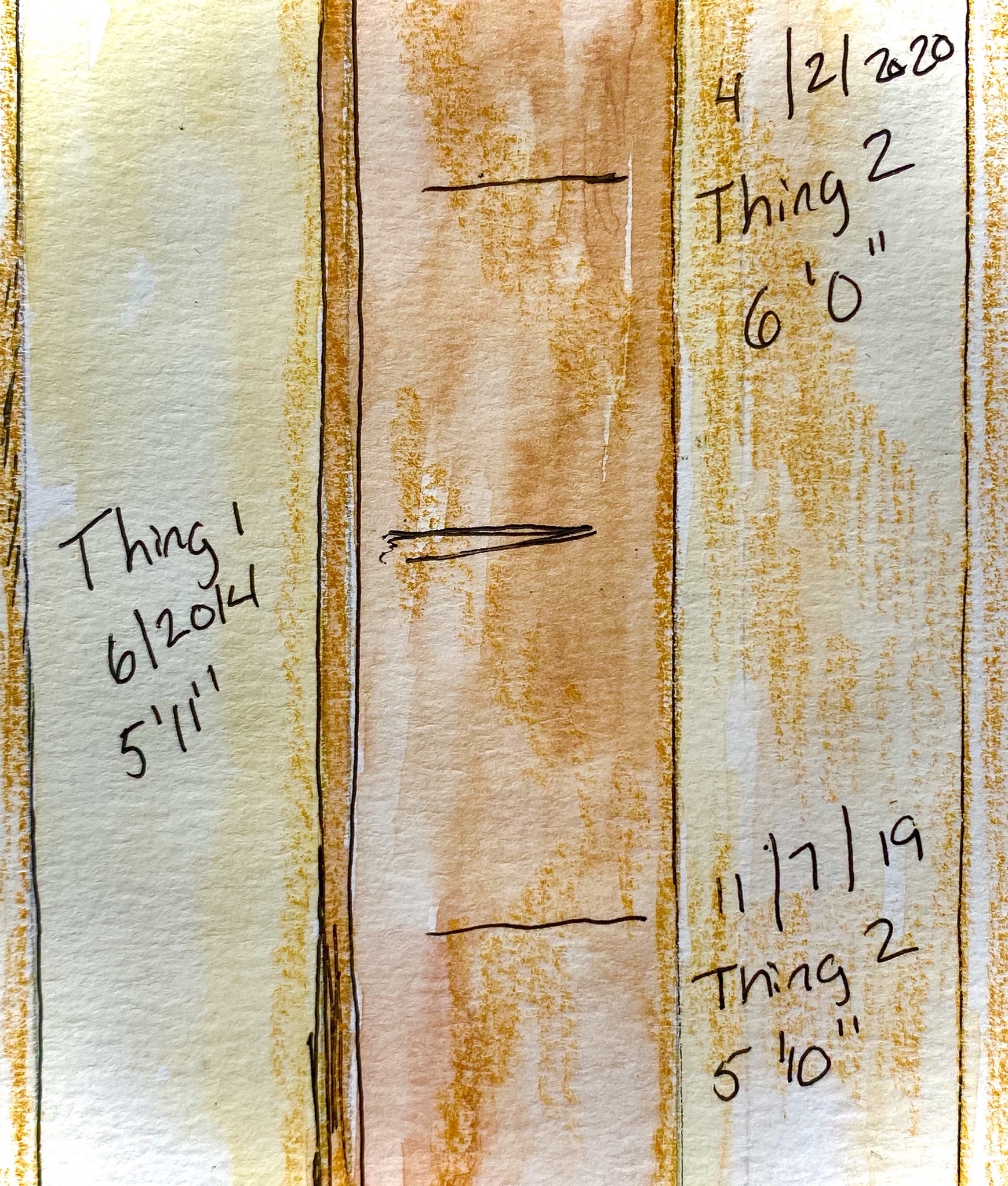

The boys have been playing catch and frisbee on our walks around the house in the afternoons. Lately when Thing2 reaches for a deliberately off-trajectory frisbee, it seems as if his feet barely have to leave the ground for him to grab it out of the sky. The boys adjusted to living apart when Thing1 left for school and then adjusted again when he came back for the quarantine, but, as Thing2 grows faster and taller than a Kentucky Wonder pole bean vine, there seems to be an another adjustment taking place.

Thing1 specifically asked for Thing2 to be born, badgering us for a baby brother for almost two years. When we granted the wish (don’t ask me what we would’ve done if it had been a sister), Thing1 enthusiastically stepped into the role of guardian/teacher/benevolent dictator. He helped coach Thing2’s Little League team. He alternately shushed and comforted him through colicky rides in the back seat.

Thing2 accepted the paradigm and fell into his role of hero worshiper without question or deviation—even when it bugged the crap out of his brother. It’s a tossup as to whether a baby brother or an actor dog is more dogged in their loyalty. He followed his brother from room to room, and even from hobby to hobby. If Thing1 was good at a sport, Thing2 had to give it a go. When his older brother built a computer, he had to build one too.

And then Thing1 left. Thing2 had to find a new hero.

Our youngest has used the vacuum to bond with the Big Guy over a shared love of music and cooking. He has learned how to tech-support himself on computer issues. He has nurtured talents he discovered on his own and become his own hero, and when Thing1 returned home from school early, Thing2 very much wanted to spend time with him. There were no repeats, however, of a little kid banging on his older brother’s door, demanding to be included.

In the mornings, they each go to their corners to work on their academics. We eat dinner in the den together, but after about 20 minutes, the boys go to their separate activities. Thing1 tries to stay in touch with his new college friends as much as possible, and Thing2 will geek out on the computer or come hang out with me.

The one time of day come they really come together if over the daily games of catch. Thing1 is still slightly bigger and much stronger, but Thing2 is now a teammate, not an acolyte. There’s less coaching and more rough-housing, but, despite the extra bumps and bruises, the gaps between my two pole beans are getting narrower.

Everyday Art

In my classroom there are long rows of hanging shelves containing multiple copies of different novels for my kids to read. Next to my little brown desk, however, I keep single copies of various books that I am reading with students one-on-one or, in my “free” Time at the suggestion of various students. My little stack of books is a colorful sculpture, an homage to the conversations I have with the wonderful young people who come through my door every day.

My and Thing1’s health situations have necessitated close adherence to the “stay home“ directive. I am treating this time at home as training for retirement when, again, there will be infinite time to write and paint as part of a last career. I’ve inaugurated a daily schedule of writing in the morning and drawing practice in the afternoon (chest pain from pneumonia still makes painting impossible).

Writing is a conversation with the zeitgeist, but, despite efforts to focus on the sparkle in the solitude, the conversation seems a bit one-sided lately. I can’t do much about the solitude, but, looking to put some sparkle in the conversation and, at least mentally, reconnect with my kids at school, I’ve started a new book sculpture next to my/Princess Jane’s fuzzy blue chair.

What do you have in your book sculpture these days?

The Song Can’t Remain the Same

I expected some savings during the quarantine from not driving, going out to restaurants or ordering takeout. I expected an equally big bump in our grocery bill when Thing1 returned to the nest, but, even with two giants to feed (13-year-old Thing2 hit the six foot mark this week), thrift, apparently, is part of our new normal. It’s one of the few welcome surprises this month.

I thought about it as I came across a video about propagating root vegetables from cuttings from store-bought veggies. Always a sucker for a recycling project, I knew I’d need a place to keep my cuttings safe from cats looking to knock things over. Before the pandemic I might’ve stopped at the garden center on my way home from work. With every project and new recipe lately, however, I find myself going shopping in my attic or the recycle bin with an eye on repurposing items that might’ve been forgotten or even tossed.

Last year I, along with a plethora of other Americans got swept up in decluttering — removing things from the house that didn’t spark joy. I quit when I got to the book stage (might as well declutter cats or kids), but I was already fumbling during the closet clean-out. I was never going to get that perfect pink size 6 dress on again, and I’m sure it found a better home with a more dedicated dieter. There were plenty of items, however, that went to donation bins whose goals of redistributing old clothing, I later learned, may be doing more harm than good.

For environmental and economic reasons, we were off grid for over a decade. We obsessed over every watt we consumed, but this sparkling solitude has made me question my own material consumption.

A few days ago I stumbled on a wonderful movie on Netflix called “The Boy Who Harnessed The Wind“. I highly recommend for anyone with kids — I even ordered bought the book for my middle schoolers for fall. The story takes place just at the time of the 9-11 attacks and follows a high schooler in Malawi named William along with his family as they endure flooding, drought and subsequent crop failures. The change in family fortunes force them to count every grain in every meal. For William, a born tinkerer who loves fixing things, the changes mean the end of school, but, consumed with a vision of wind-powered irrigation for the village, he sneaks into the library to conduct research on his own.

There are so many powerful themes throughout the movie — strength, family in all its complexity, perseverance, and the power of education – but, as I watched William rummage through the village landfill for scrap metal and used electronics to build his turbine, another, smaller, theme emerged. Education, not merely necessity, was the mother of William’s inspiration, but it was thrift and ingenuity that helped him use whatever was on hand to bring together his turbine and save the village.

Now, a year after my failed purges, I am rethinking every purchase and every creation in terms of its embodied energy and its impact on our budget. The purge got me thinking about what happens to those things when we’re ‘done’ with them. Watching a determined teenager cobble together a life-saving machine with recycled parts, however, provided a sober — and inspiring – new perspective that will make me consider much more carefully exactly when I’m ‘done’ with something and when it still has another life left in it.